|

| Silk weaving in traditional hand looms in Pilikothi |

For any visitor to Varanasi, Godowlia market is a fascinating place to be. This oldest market of Varanasi is a treasure trove for a variety of local artwork and craftsmanship. While for people in the know it is a shopping haven, for the uninitiated, it is a threatening tourist trap. The keen buyer, looking for the renowned silk of Varanasi are ambushed by pushy salesmen at every step, their presence impossible to ignore. They tempt with the promise of cheap buy along with an opportunity of visiting a local factory, thus trying to prove the authenticity of the goods offered. Any unfortunate soul falling prey to this menace will indeed be shown a factory, where mass production looms spin out bright coloured fabrics from synthetic yarn. A purchase is obligatory, and the fabrics on sale are far from the quality of silk and craftsmanship the weavers of Varanasi are known for.

With the markets flooded with counterfeit Varanasi silk, the discerning shopper hence heads to the reputed shops as a safe bet, paying a premium price for their assured authenticity. The genre of the skilled weavers of Varanasi is gradually dying out. The high cost and skill required for weaving a true Varanasi silk is further worsened by the competition it faces from the technologically advanced textile regions of India. However, some still remain in the nook and corners of Varanasi, fighting to survive and save a dying art.

|

| Yarn for weaving |

From Godowlia crossing, a short auto ride took us to Maidagin crossing. Changed over to a second auto to Pilikothi. The auto driver was curious about our destination and purpose of visit. It did not surprise when he wanted to take us to his own factory. More often than not, every auto driver in Varanasi is connected to a shop, either his own, or of his cousin, or a friend and will try to persuade a visit. I was armed with a name - Haji Khalilullah Mohd Din, which I had bumped into on the internet, and saved us the hassle.

Varanasi, despite being known as the holy city of the Hindus, is actually a beautiful amalgamation of all religions. Approaching Pilikothi, the change in the religious landscape was obvious. The mosques, which are dotted around Varanasi, appeared more frequently in close proximity here. The roadside shop names proclaimed their owner's religion. Traditionally the delicate weaving of the Varanasi silk has been the realm of the Muslim households, the art handed down through generations of proud weavers.

|

| The narrow, dusty lanes of Pilikothi reverberate with the sound of the semi automatic looms |

|

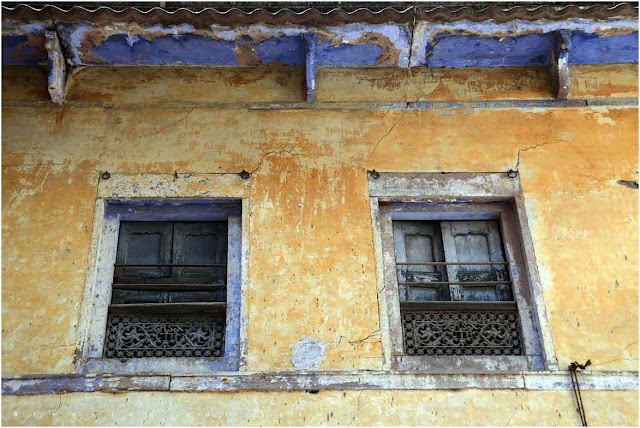

| The houses are over a century old |

The neighbourhood is a favourite haunt of every retailer across the country. Purchases are made at wholesale prices and sold at a premium in fancy air-conditioned shops. Hence, as we entered, the first thing we wanted to clarify, we were definitely not sellers. Our purpose of visiting Pilikothi was out of interest and possible purchase for personal use. We received a warm welcome by the whole family and were seated in the gaddi, the shop floor where business was conducted. The sound of the working looms rumbled on as rich tea was served.

|

| In-house store set up in the gaddi |

The finished goods were laid out on the covered floor - sarees, dupattas, dress materials, scarves. Though some were in beautiful soft silk, the use of other natural fabric in sarees was apparent. Pure silk is expensive, requires maintenance and worn only on special occasions. As a result, they have dropped in popularity in recent years. The more contemporary use of cotton and part mixed silk is a much desired choice, especially since they retain the speciality of the Varanasi weavers in their beautiful traditional patterns.

|

| With no background on textiles, it was educational getting an insight into the industry and its working |

|

| The traditional Varanasi silk designs |

|

| The designs from the in-house designer. I deliberately blurred them out to respect their trade secret |

|

| The fabric for a dress material lies around, freshly weaved |

|

| The threads still need to be trimmed |

|

| The semi automatic loom creates the designs from the punch cards |

|

| The punch cards upclose |

|

| The weave is automatic, needing some human intervention |

|

| The looms cannot weave the delicate silk, but churn out other fabrics efficiently |

I could hear the subtle knocking of wood as my eyes adjusted to the dim light. On the other end of the room, a weaver was working on a hand loom, creating a bright red fabric which was glistening in the low light. The woven length was rolled up inside a plastic sheet for protection.

Weaving a standard silk saree can take about a fortnight. He had spent the previous four days working only on the pallu. For the weavers working on the hand loom, the weave design which we earlier saw programmed in a punch card, is set out in their head instead. A single mistake and the whole saree would be unsuitable for selling. Hence the need for darkness and the complete silence to help his concentration. We were feeling guilty about out intrusion and was hoping we weren't the cause of a disturbance to his tenacious routine. We thanked and made a quiet exit.

|

| Hand loom weaving requires much skill and concentration |

|

| The silk threads |

We made a few purchases at the premises, but not of the famed silk and instead settling for the cotton ones. I loved the silk scarves woven in self patterns, so purchased a few as I could own a small piece of the lovely fabric without breaking a bank. The stock in their in-house shop was limited compared to what is expected in a retail shop. But we knew that what we were looking at was genuine craftsmanship, created lovingly by a family struggling to keep a dying art alive. However, the best way to make purchase is to look out for new products which Sufiyan posts regularly on their web page. The goods can be ordered online and are delivered throughout the country. Needless to say, they disappear fast. The details are given below.

Speaking to Sufiyan, and visiting the family changed my perspective of the weaver community in Varanasi. I could see how much this traditional craftsmanship meant to all the families in the locality. Also as like any other industry, it is more than just the weavers who make it work. Starting from the preparation of the yarn, once a saree is woven, there still remains a multitude of labour intensive activities for it to be considered a finished product. Unfortunately, the dying industry is also casting a shadow on these ancillary industries as more and more people are put out of job everyday.

The cost of running the looms is high. The machines need daily maintenance check as a single slip up can destroy the whole weaving. They are in dire need of a technology upgrade which the weavers cannot afford. While visiting the weaver community was an enriching experience, it also definitely created a sadness within. But what fascinated me was despite all their struggles, we were still greeted with an openness and warmth I didn't expect and was left speechless with gratitude.

Haji Khalillulah Mohd. Din

Web page: Haji Khalilullah Mohd. Din

Facebook Page: Orchid Silk

Here is a video I had posted on Facebook from my visit: Pilikothi - Varanasi

For more stories and photographs from Varanasi and rest of the world, please follow me on Facebook and Instagram - Breaking out Solo